Author

Muriel ten Brummelhuis

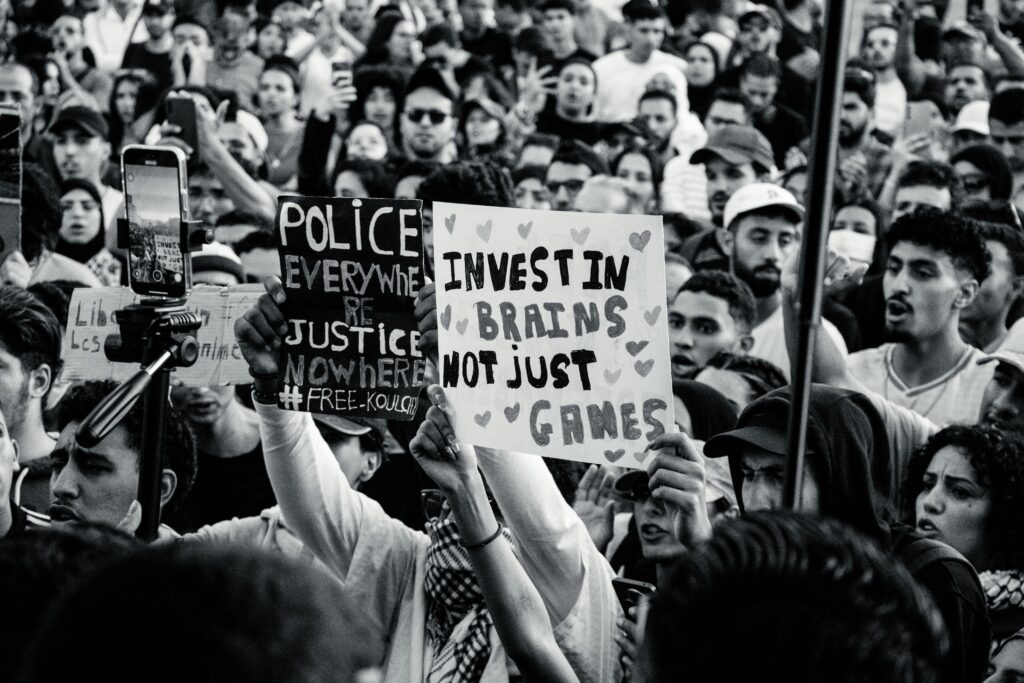

Morocco has been witnessing a series of youth-led protests, driven largely by Gen Z. While grounded in past struggles for justice and dignity, this mobilisation is also part of a broader global, digital and decentralised phenomenon. D66 International spoke to investigative journalist Kenza Sammoud about how Morocco’s Gen Z is reshaping civic participation, and what this means for the country’s future.

Muriel ten Brummelhuis

Beeld: Ayoub Galuia

Kenza: ‘The current wave of youth mobilisation in Morocco reflects both a continuation and an evolution of earlier forms of civic expression. Each generation has found its own way to voice aspirations and frustrations, from the struggles for justice and dignity during the Years of Lead, a period of the rule of King Hassan II of Morocco, to the social and political awakening of the February 20 Movement, in the time of the Arab uprisings, and later the civic demands expressed during the Hirak period, characterised by mass protests in Morocco’s Rif region. These moments have built a collective awareness that still influences how young people perceive participation, justice and citizenship today.

What we are seeing with Gen Z is a new language of engagement. Many young people choose to express themselves through art, social media, volunteering, and community initiatives rather than through formal political channels. This is partly because they feel disconnected from traditional institutions and political parties, which they often see as unrepresentative or unable to address their concerns. Their activism instead focuses on issues that affect their daily lives: employment, education, equality, environment, and social inclusion, and they link these to broader global values.

Unlike previous movements, this generation tends to be more digital, creative, and decentralised. Their actions are not always framed as protests but as ongoing forms of participation: online discussions, local campaigns. In that sense, the new wave of youth mobilisation is both a legacy and a reinvention: it continues Morocco’s long tradition of civic engagement but adapts it to the realities and tools of today’s world, where young people are seeking new, more authentic ways to make their voices heard.’

Kenza: ‘The decision to invest heavily in football infrastructure ahead of the 2030 World Cup touched a sensitive chord because it came at a moment when many young people are struggling with daily challenges: unemployment, access to housing, rising prices, and limited opportunities. For a large part of society, especially the youth, this contrast between visible large-scale investments and personal economic hardship created a sense of imbalance and frustration.

Symbolically, the issue goes beyond football itself. For many, it represents the gap between national ambitions and individual realities. Young people admire Morocco’s growing international visibility and feel proud of its achievements, but at the same time, they hope that similar attention and resources will be directed toward education, health, and job creation.

In this sense, the reaction is not a rejection of progress or sports, but rather an expression of a desire for development that feels closer to people’s everyday lives. The stadiums became a symbol, not of sports alone, but of broader expectations: that Morocco’s success on the world stage should translate into tangible improvements for its citizens at home.’

Kenza: ‘There is clearly a generational and technological gap in how young people and institutions communicate today. Morocco’s youth live in a digital environment. They learn, work, and express themselves online. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and X have become spaces where they discuss social issues, share ideas, and build communities. This digital fluency allows them to mobilise quickly and to connect local concerns with global conversations.

Meanwhile, many institutions still rely on traditional, top-down forms of communication, which can make them appear distant or unresponsive. It’s not always a matter of unwillingness, but rather of different rhythms and languages. One generation moves in real time and expects dialogue, while the other often works through slower bureaucratic or formal channels.

This disconnect shapes the dynamics of mobilisation and response. When young people don’t feel heard in official spaces, they turn to digital ones; when institutions don’t fully understand those spaces, messages can be misinterpreted. The result is often tension rather than dialogue.’

Kenza: ‘It is still too early to predict how things will evolve, but what’s happening in Morocco and across the region suggests a deeper generational shift rather than a passing moment. Young people today are more connected, creative, and globally aware than ever before. They want to contribute actively to shaping their societies, not only through protest, but through innovation, civic initiatives, and new forms of expression.

The upcoming elections in 2026 will be an important moment to observe whether this energy can be channelled into constructive participation. If institutions and political actors succeed in opening more inclusive spaces for dialogue and engagement, it could help renew trust and strengthen participation. But if young people continue to feel excluded or unheard, we risk seeing a widening gap in youth participation, which could eventually affect voter turnout and representation.

Across Morocco this reflects a wider generational reckoning, not just with politics, but with the meaning of citizenship and accountability in a changing world. The challenge now is to transform this collective energy into shared progress, where youth feel both empowered and included in the future of their country.’